Creativity as a Search Problem: A Speculative Mental Model

November 21, 2019

One of my hobbies is writing, recording, and producing music. Unfortunately, I have often been hit by something like creative block. The two ways this primarily manifests is on the one hand as a lot of barely started projects1, and on the other as more developed ideas where I simply ran out of steam. Most often cases in the former category don’t really amount to anything: when or if I do return to them later there usually isn’t really enough material to provide much more inspiration than an empty project. Indeed, the amount of work required to finish such a barely started project is nearly the same as just starting from scratch. This is in contrast to cases in the latter category which are actually quite likely to get finished some day. My most recently uploaded track, as of this writing, is the finished version of a project I started in April 2018. The majority of elements were already there, in a rougher form than in the final track, and all I really had to do was improve some of the sounds, do some mixing, add some polish. The newly added content was minimal.

The contrast between these two cases is kind of interesting. While the false starts may have in some instances represented ideas that seemed promising at the start, I think most of the time they are pretty much just failed experiments. Especially when you are new to something, such failed experiments are an inevitable part of the process. On the other hand, the near finished projects were obviously promising enough to warrant being taken so close to completion. While you still got stuck, the time away works to your advantage: whatever road block you hit that kept you from finishing the thing in the first place is long forgotten. So instead, you get a great start of an idea to which you can apply your refreshed—and in the interim, likely refined—creative process. The process of finishing can in such cases be a pleasant experience of applying your skills without the more taxing process of trying to shape an entire work from scratch.

In between these many incomplete projects and failed experiments are the works of inspired creativity—something which I imagine has tormented anyone who does any kind of creative work. The work seems to flow out of you naturally, joyfully. Indeed, one might be tempted to think of this state as being synonymous with creativity. But alas, it is unreliable, coming in erratic bursts. To be prolific, most of us can’t wait for this kind of inspiration.

An interesting observation is that the process of completing the unfinished track I talked about above was a little bit like those experiences of inspired creativity. There was never really any creative block. I just got to work on the next thing until the track started to feel finished.

Destinations and Exploration¶

SeamlessR, a music producer who also makes youtube video tutorials, touches on this in Ammunition and Experience. There are at least two ideas in that video. First is that experience provides a kind of ammunition in the form of an intuition as to where things can go at different stages of a project. The other is that given an idea, experience also provides the knowledge needed to move in the right direction to realize that idea. Though experience is given as the key in both cases, the two are very different: the first is about knowing your destination, and the second is about having the skills to actually get to it.

It is worth pointing out that these are not really mutually exclusive. Once you pick a destination, your experience gives you a sense of how to get there. As you start to move in that direction the new context gives you new ideas. Some of those ideas change your target destination. And so on. This cycle of choosing a direction, moving a bit, then reevaluating that direction, starts to sound a lot like a search process like gradient descent. A gradient descent optimizer looks for peaks or valleys (depending on if it is minimizing or maximizing) in some function by cycling back and forth between finding the direction of steepest descent/ascent at the current location, and taking a small step in that direction.

Through this lens, the creative process is a kind of search for “pleasing” points—for some subjective definition of pleasing—in an extremely high dimensional space.

This is in some sense literally true. Sticking with the music production example, if you look at a typical digital audio workstation, it is essentially this big array of knobs and dials and sliders and curves and midi/audio data that can be manipulated in all kinds of context-specific ways, and that all affect what the end result will be when you ultimately press the play button. Our job as the producer then, is to find the right spot in the space of possible configurations of all these controls to produce an end result that is pleasing.

Not only is the space huge and high dimensional; much of it is degenerate or pathological. That is, many of those configurations of knobs and sliders and curves and data will be mostly the same—I can synthesize nearly identical sounds in multiple ways for example—and many others will be akin to noise, or too unpleasant or chaotic to be desirable. Making matters worse, even if we could learn to perfectly avoid the degenerate and pathological parts of this space, what remains is still too daunting and incomprehensibly large to be able to just aimlessly explore and happen upon something pleasing2.

The role of experience in this framework is then to provide two kinds of knowledge and/or intuition which guide the search process:

- Knowledge of potential destinations: experience develops awareness and intuition about pleasing regions of the space that can help define and refine target destinations. This is essentially the first kind of ammunition discussed by SeamlessR.

- Navigational knowledge: experience teaches you to read local cues and navigate nonlocal jumps to target destinations in this complex space. This corresponds to the second type of ammunition from the video.

Understanding the Experiences of Creative Work¶

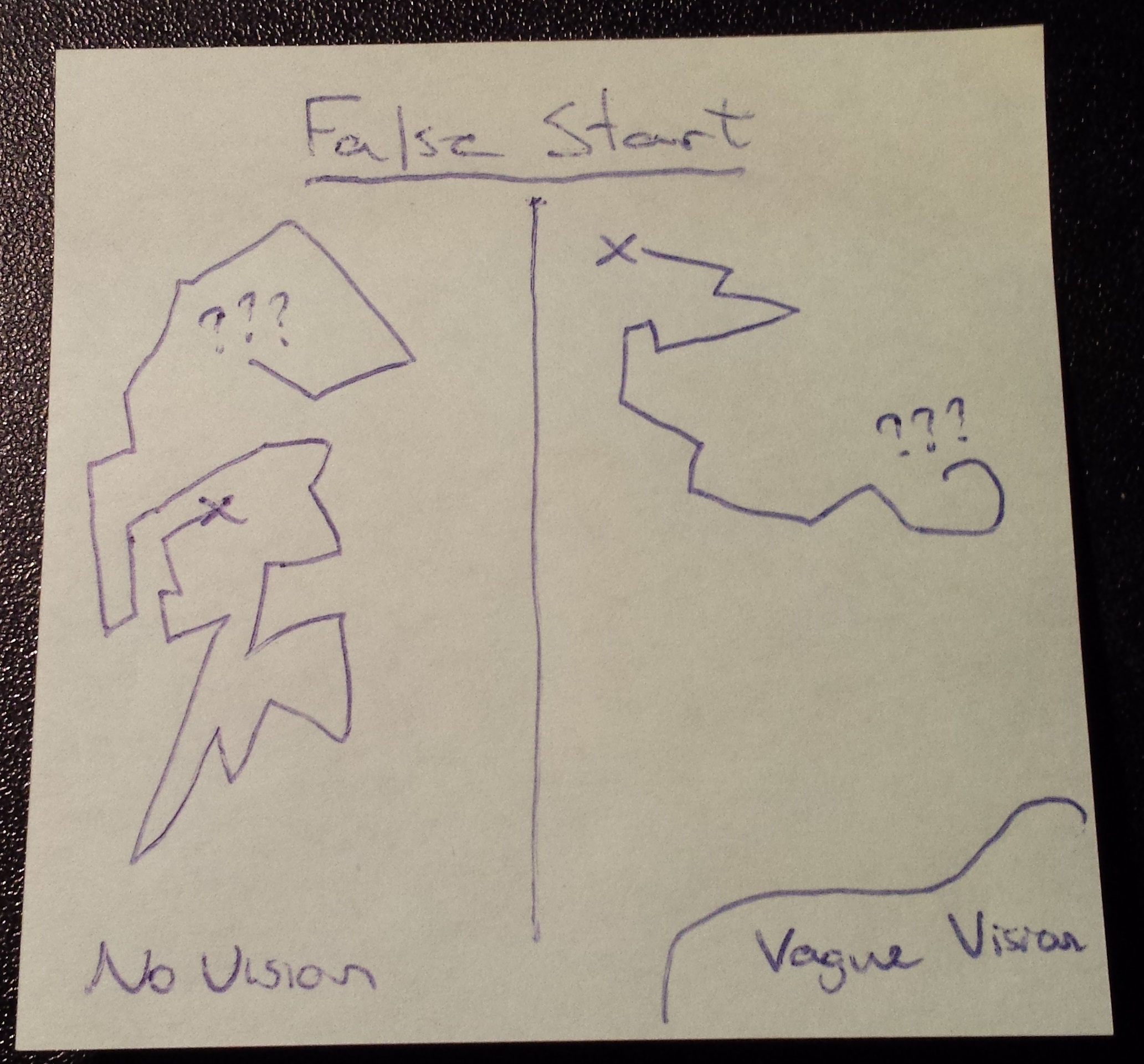

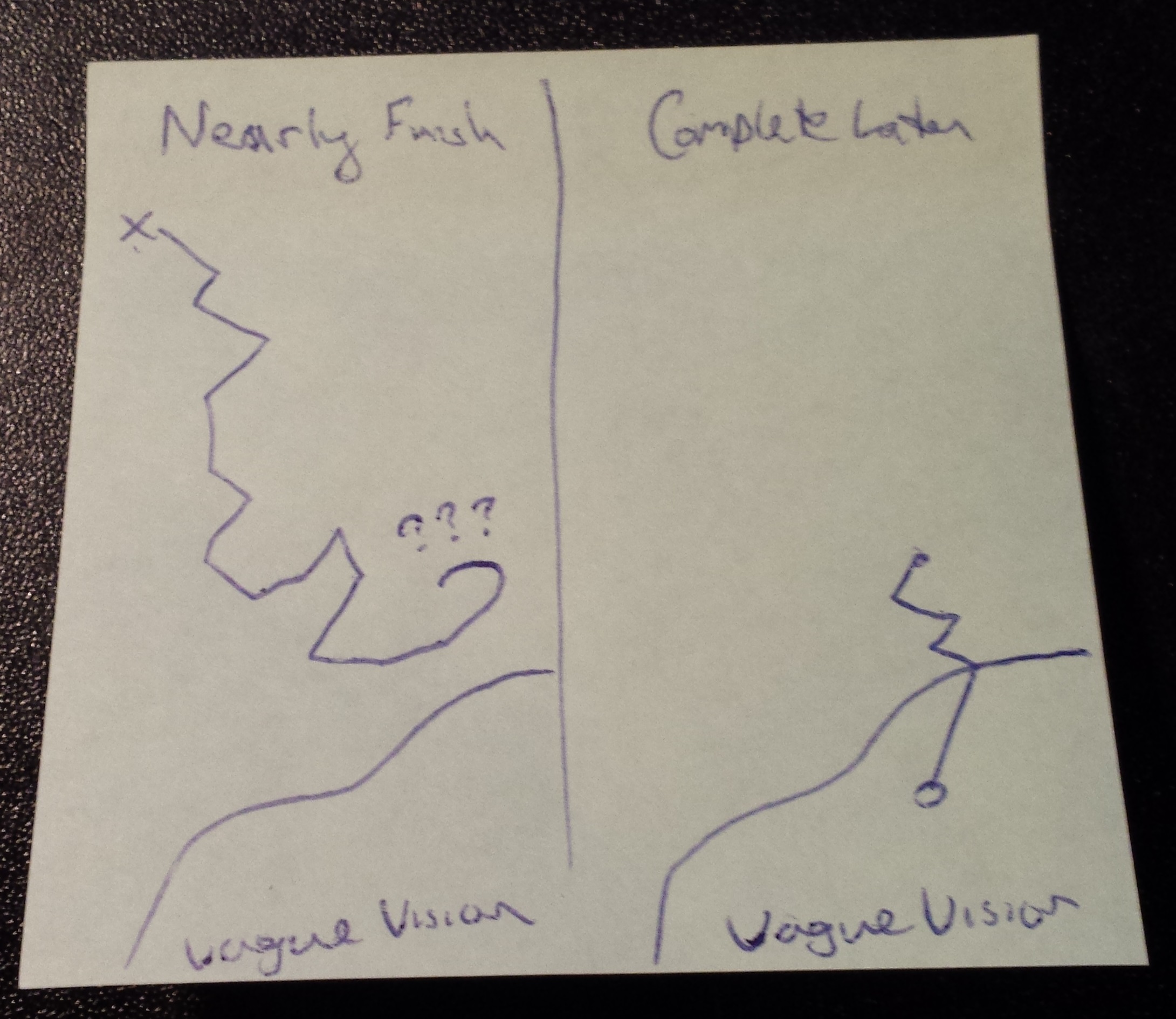

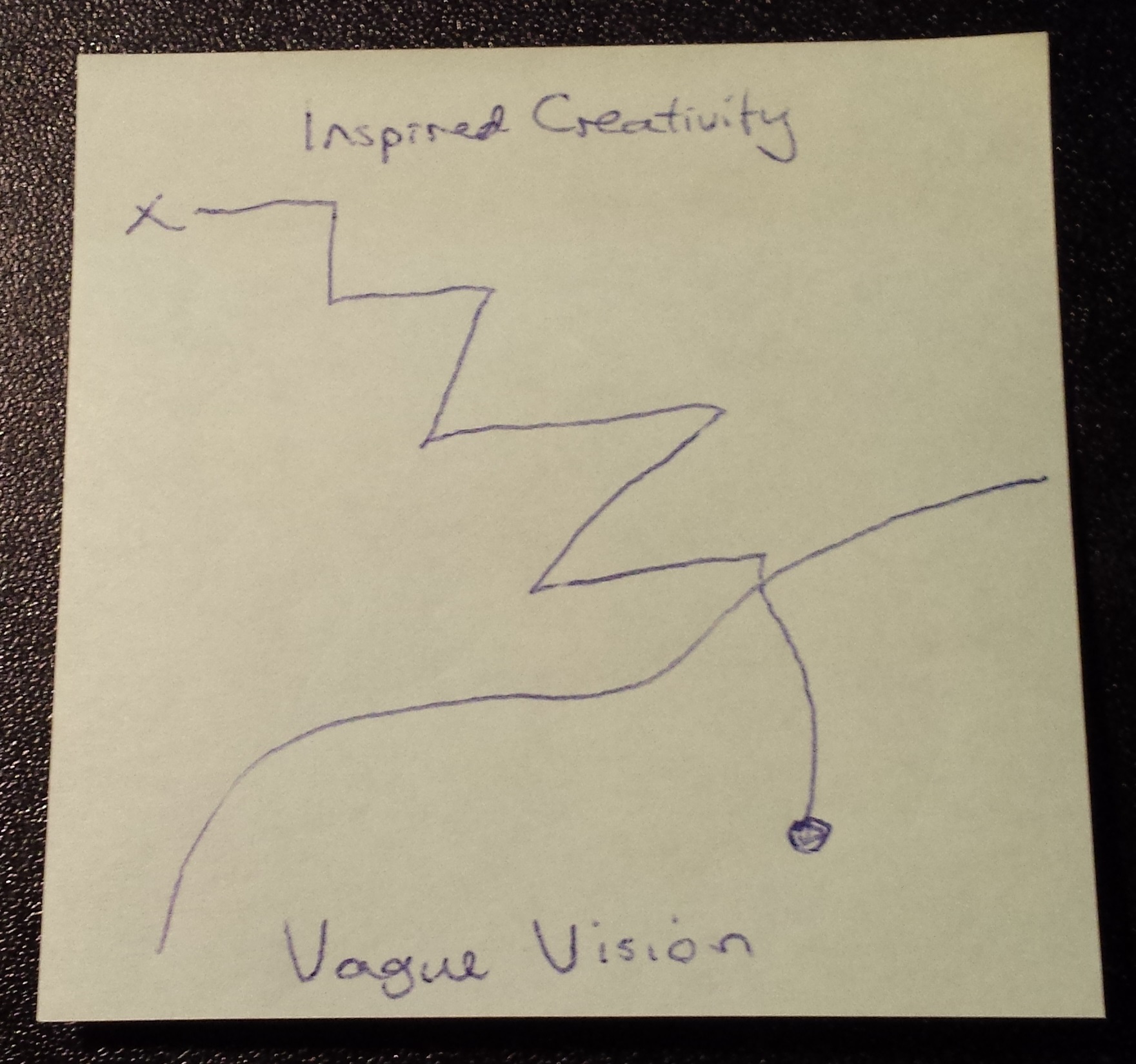

We can employ this model to try and understand the three common experiences of creative work mentioned above: false starts, nearly-finish-complete-later, and inspired creativity.

The false start could manifest in a couple ways. First, without any real vision of what we want to create early on, we might wander about a little bit, fail to come up with an idea, and then give up. On the other hand, maybe we do have some vague vision early on, but lack the required skill to navigate toward that region of the space successfully. Instead, we set out in our best guess of the right direction, but quickly get lost.

The nearly-finish experience manifests as having a vision for what our destination is (whether it came from inspiration or exploration) but then getting lost after getting most of the way there. When we come back to complete the work later, we are reminded of the vision, and, starting much closer, are able to make our way there with relative ease. That said, we may, if we don’t yet have enough experience to realize our vision, still not be able to get unstuck.

Finally, inspired creativity looks a lot like the complete-later phase of the previous case. The only difference is the journey from start to vague vision is longer. But if the vision is within our grasp at our current experience level, we are able to navigate into the general region fairly easily.

In the cases where we successfully make it to the region of the space evoking the creative vision (marked “vague vision” in the diagrams), the search becomes easier. We are where we want to be, roughly, so it is a matter of finding the nearest local optimum in the “pleasing” field and calling the work done. In the diagrams this is represented by the path going from zig-zaggy to relatively direct.

In contrast, when we get stuck, we are essentially trapped in some not-very-pleasing region of the space, where we are unable to determine how to move to improve the situation, or get closer to our vague vision if we have one. The result is a kind of overwhelm in the face of ambiguity and high uncertainty.

Don’t Get Stuck¶

Perhaps this is not such a revelation, but creativity is a fundamentally a productive activity. And therefore, to do creative work, you must work. Productively. And nothing hinders productive work like uncertainty.

If the creative process is looking for pleasing points in a super high dimensional space, uncertainty occurs when we are unable to distinguish local directions in order to continue making progress. In the optimization metaphor, we are trapped in a peak or valley—that is, a local minimum or maximum. Flailing about to try and get out of such a peak or valley is hard for a typical optimizer, so it is better if you can avoid getting stuck in the first place.

From the model of inspired creativity above, it seems the best way to avoid getting stuck would be to have a creative vision that is realizable given our current level of skill. You can imagine the vision as putting a large bias in the “pleasing” field against points outside a particular region that we can then use to navigate toward that region. The skill/experience component is still critical: if we don’t have the experiential skills to navigate to the target region, the bias doesn’t help, because we can’t translate the cues it is giving us into actual directions. But assuming we do, once we get there, we go into ordinary optimization mode and find a local optimum.

So then how do we find a vision?

As discussed above, there is a feedback cycle between moving in the space and refining the target destination. It stands to reason then, that one way to find a vision is just to explore, and see what happens. And perhaps, if generating a vision purely through exploration is reliable enough with sufficient experience, then that is why some highly prolific artists say creative block is bullshit. But in my experience this aimless exploration can also lead to a lot of failed experiments. So for the rest of us, with the framing we now have, perhaps we can consider some other methods to try and bootstrap a vision when we lack organic inspiration.

Artificial Constraints¶

Constraints can help break creative block. Most people are familiar with this in the form of time constraints. When deadlines loom, it seems to help us get started. This is Parkinson’s law: “work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion.” But as Anne-Laure Le Cunff writes in a post on exploiting Parkinson’s law:

Researchers found that when people face scarcity, they give themselves the freedom to use resources in less conventional ways—because they have to. The situation demands creativity which would otherwise remain untapped.

Perhaps this is why some game developers find constrained platforms—like the Pico-8 fantasy console—so freeing. There are all kinds of decisions that constrain the design space of possible games for the platform that you as a developer simply don’t need to make.

Within our mental model we might explain this phenomenon by observing that, when developing a vision, artificial constraints make the exploration process less overwhelming by reducing the dimensionality of the search space. As we start to develop a vision, if our chosen constraints play to our existing strengths, they could also help make the navigation process less prone to failure.

Combinatorial Creativity¶

“Combinatorial creativity is the process of combining old ideas to come up with something new”. In our mental model, I think this amounts to taking some points or specific regions in the space, and asking: what might a subspace that contains all these points look like? And within that subspace, what are some other interesting and unique regions that I can explore?

On one hand, by letting us think about regions of a subspace, a combinatorial approach helps us develop a vision in a relatively direct way. On the other hand, once we get to the general area, the subspace also acts as a constraint on the optimization process. Further, we can tailor the vision to our skills by choosing appropriately technical examples to start with. For this reason, I wonder if this might be a particularly powerful approach when working in a new, unfamiliar space.

Start With Abundance¶

In How to Cure Writer’s Block, David Perell recommends you “start writing once you have so much information that you can’t not write.” Echoing SeamlessR above, he quotes Sebastian Junger: “‘If you have writer’s block, you don’t have enough ammunition.’” The fundamental idea behind the post is to take notes about your ideas and reference materials as they come in, and write once you’ve got enough material to make the process easy.

In my reading, the recommendation is that the creative work, that is, the writing, should not start until the creator has a big enough reserve of context to resolve the ambiguity of starting. This gives you lots of directions and ideas to explore while developing the vision for your own contribution.

Fundamentally, there is probably no mental model or technique that will just keep you from ever getting creative block again. If there was a simple formula, it wouldn’t really be creative, would it? And even if there was, you’d still have to deal with motivation, and finding the time, and a million other things, surely.

But I have found that this model helps me reason about some of the problems I’ve had in my own creative projects, and provides a nice framework in which to think about and compare a lot of the common advice for boosting creative output.

I also like that experience plays such an important role in the model in order to successfully navigate the space. It’s a reminder that if you do get stuck, the best thing to do is just keep trying. Practice. Do more failed experiments. Try finishing something even if it doesn’t seem that great. Roll with it anyway and see where it goes. You might surprise yourself. And remember that quantity beats quality when doing is the best way to get better.