Boredom World 2: The Role of Orientation in Overcoming Overload Boredom

August 16, 2020

This post is part of the Boredom World blogchain:

July 23, 2020 – Boredom World 1: Boredom, Overload, and Meaning Collapse

In a couple of my most recent posts, I’ve been gesturing at the notion of ephemerality as a source of overload and anxiety, and trying to determine some strategy for alleviating it. Here I’m going to give this problem a new name: boredom.

August 16, 2020 – Boredom World 2: The Role of Orientation in Overcoming Overload Boredom

Last time we developed a generalized notion of boredom as the inability to make a decision. In this post I focus in on boredom induced my exposure to an ephemeral environment, and propose a model of what solutions to such a problem might look like.

October 27, 2020 – Boredom World 3: Overcoming the Hastings Limit By Bootstrapping a World-View

The Hastings limit is what you hit when there is simply far too much content for you to ever get to it all. Here we talk about overcoming this problem by bootstrapping a world-view from the bottom up.

November 14, 2022 – Boredom World 4: You can't "do anything", so do what you can

In this post, I apply the concept of an orientation to career choices, using a case study from Meg Jay’s book, The Defining Decade.

The following, due to Orrin Klapp, gives the beginnings of a mental model for this generalized notion of boredom I introduced in the last post:1

Meaning and interest are found mostly in the mid-range between extremes of redundancy and variety – these extremes being called, respectively, banality and noise. Any gain in banality or noise, and consequent meaning loss and boredom, we view as a loss of potential … for a certain line of action at least; and loss of potential is one definition of entropy.

If this is right, and the anxious boredom produced by exposure to an ephemeral environment is indeed the result of too much variety of input, the obvious solution is the intentional introduction of redundancy – the introduction of some structure atop the ephemeral stream.

In my post discussing Paul Graham’s bus ticket theory of genius, I refer to such a structure as a scaffolding – greedily built up from a series of structure preserving transformations using the ephemeral stream as source of raw materials. By gradually building up such a scaffolding we develop a point of view that imposes structure and meaning onto this otherwise unstructured environment. We begin to see ways to integrate the raw materials that float by into our scaffolding, and as the structure grows and becomes more elaborate, the opportunities for growth themselves become more frequent. Through the lens of this structure, we can begin to make sense of the environment, to understand it, and therefore overcome boredom, understood as the inability to make a decision.

But there is still something missing from this overall all account – something I will refer to as orientation.

Broadly speaking, an orientation is some specification of direction relative to a given position. For the present model then, I’ll use orientation to refer to some possibly vague, directional sense of how we are trying to grow our scaffolding. It is a filter both on the items we draw from the ephemeral stream itself, and on the transformations we choose to apply to the structure.

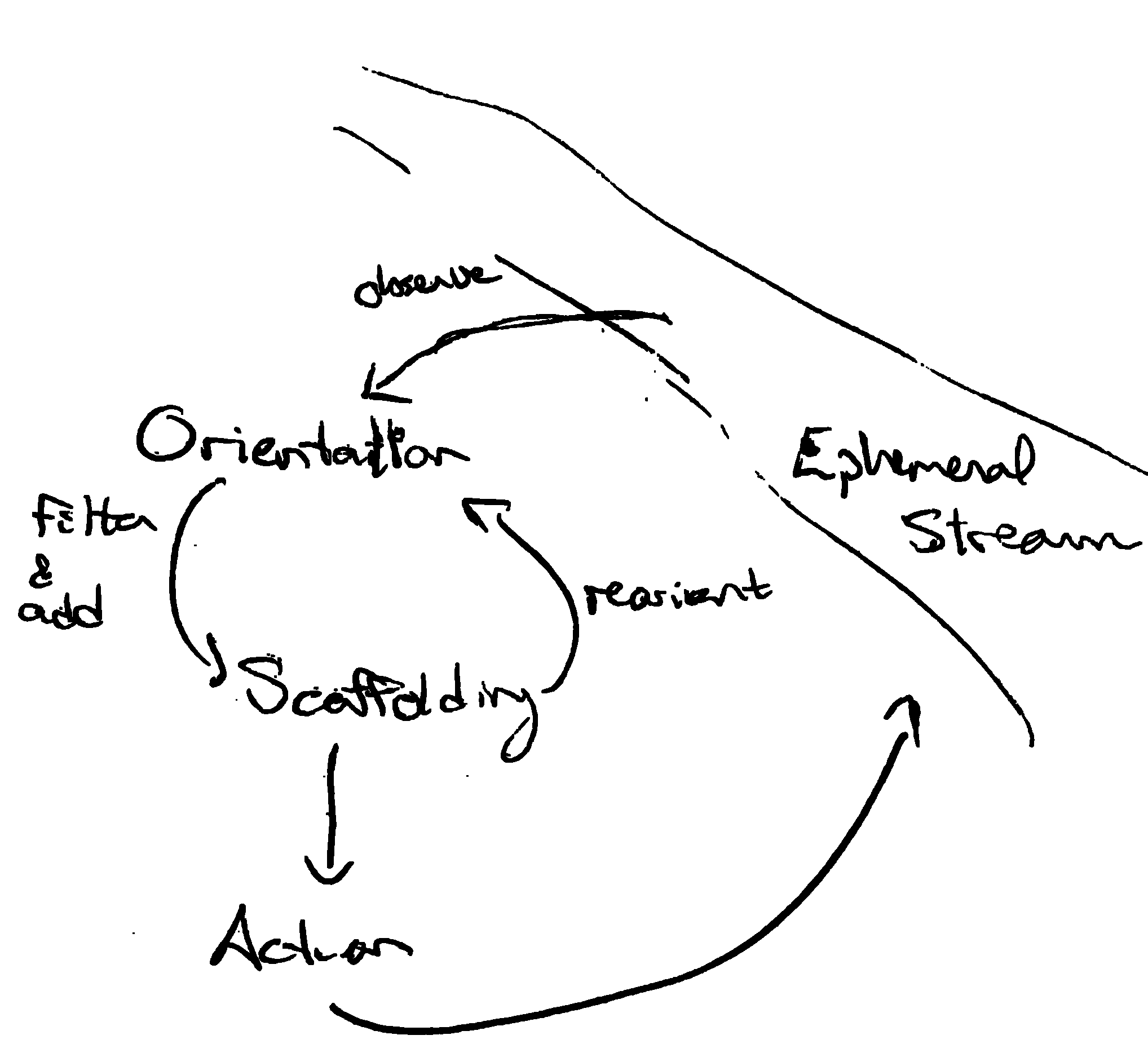

Putting it all together, we get a mental model what a strategy for dealing with this kind of ephemeral environment might look like. As inputs are drawn from the stream, they are filtered and integrated into our scaffolding through our orientation. As this scaffolding develops, so too does our orientation. Finally, through the lens of this scaffolding we are able to make decisions and take actions, which themselves influence the ephemeral stream.

Intuitive Orientations¶

In my original post exploring some of these ideas, I refer to the role of serendipity in alleviating anxiety produced by ephemerality. I think with this notion of an orientation, we can further clarify this role.

In particular, looking broadly at the work of Tiago Forte, whom I drew upon heavily in that initial post, there is an emphasis on resonance and serendipity as a means of feeding and tending your second brain. He suggests that when reading and taking notes, you should save those things that seem to resonate. Notes themselves are taken in raw form, saved, and when they serendipitously resurface in the process of some project, you can further tend them through the process of progressive summarization.

The second brain here is an external instantiation of the scaffolding, and resonance and serendipity combine to form a kind of intuitive orientation to select raw materials, and transform the existing structure, respectively. The direction here is not defined so much by some actual intended outcome or destination, but instead, an emergent direction determined by the following of the intuitive sense of what resonates, what already exists, and what resurfaces.

Now let’s return to the bus ticket theory. For Graham, the key component of this theory is a “disinterested obsession with something that matters”. Crucially though, whether the thing matters tends to be revealed after the fact. During the actual process, the disinterested obsession may well appear to be, like bus-ticket collecting, with something inconsequential. In terms of the subjective experience of being inside this process, that the object of obsession is something that matters is actually irrelevant. While doing the work, the obsession manifests as a kind of focus – a straightforward filter on the ephemeral stream that works by ignoring most things, and focusing very hard on a small subset of things. The structure emerges through simply following this intense curiosity, naturally noticing connections in the process of collecting and revisiting gathered materials.

The obsession functions as an orientation in exactly the sense I am describing. And as an orientation, I think it works very similarly to the resonance and serendipity approach, except the state of obsession probably leads to a much more focused set of things that resonate, and thus that get integrated into the scaffolding. The work itself, though, is still driven by intuition and curiosity. The rest is then largely up to luck – that the collecting and connecting leads to some breakthrough, and that the subject matter turns out to be important.

Go Forth and Become Great Scientists!¶

This is the provocation concluding Richard Hamming’s classic talk, You and Your Research. This is an orientation in a more direct sense: a constraint on the direction in which you want to take your work in the form of the quality you want it to have, namely, greatness.

I think Hamming gives a couple of concrete pieces of advice in terms of what such an orientation should look like:

- Actively think about the important problems in your field.

- Have the courage to work on significant things, and then work hard with drive and emotional commitment.

- Reframe the work you already have to be more important or impactful.

But that the orientation is more intentional does not mean that there is no element of luck: “the particular thing you do is luck, but that you do something is not.”

No matter how intentional, the orientation is only a kind of directional guide – a north star. There is no escaping the element of luck inherent in that one may only build with the materials one comes across. It is no accident that both Graham and Hamming invoke Pasteur: luck favours the prepared mind.

Broadly, I think this notion of orientation, and the model that is gradually being built up here, may give a useful lens to think about anxiety and overwhelm induced by ephemeral environments. It gives us a kind of recipe for designing executable strategies to alleviate boredom, or avoid it altogether. By orienting ourselves in a particular context, we can follow the process, and trust that the scaffolding that gradually develops will allow us to make sense of the ephemeral environment we occupy.

The orientations I’ve discussed here have largely been about intellectual progress in an information-dense context – and thus focused on alleviating information overload. But as I’ve said, I think this pattern of ephemerality-induced anxiety, or overload boredom, manifests in other areas of life as well. I expect that future posts in this blogchain will try and investigate some of these.

-

Klapp, O. (1986) Overload and Boredom: Essays on the Quality of Life in the Information Society, Westport, CT: Greenwood. (h/t Mosurinjohn, S. “Overload, Boredom, and the Aesthetics of Texting.” In Michael E. Gardiner and Julian Jason Haladyn (Eds.), The Boredom Studies Reader: Frameworks and Perspectives, pp. 143-156. New York: Routledge, 2016.) ↩

Boredom World

July 23, 2020 – Boredom World 1: Boredom, Overload, and Meaning Collapse

In a couple of my most recent posts, I’ve been gesturing at the notion of ephemerality as a source of overload and anxiety, and trying to determine some strategy for alleviating it. Here I’m going to give this problem a new name: boredom.

August 16, 2020 – Boredom World 2: The Role of Orientation in Overcoming Overload Boredom

Last time we developed a generalized notion of boredom as the inability to make a decision. In this post I focus in on boredom induced my exposure to an ephemeral environment, and propose a model of what solutions to such a problem might look like.

October 27, 2020 – Boredom World 3: Overcoming the Hastings Limit By Bootstrapping a World-View

The Hastings limit is what you hit when there is simply far too much content for you to ever get to it all. Here we talk about overcoming this problem by bootstrapping a world-view from the bottom up.

November 14, 2022 – Boredom World 4: You can't "do anything", so do what you can

In this post, I apply the concept of an orientation to career choices, using a case study from Meg Jay’s book, The Defining Decade.